The Language of Detention

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

Enemy combatants. Enhanced interrogation techniques. Indefinite detention. The language we use to communicate Guantánamo’s recent history is both legally precise and frustratingly indirect. It also comes loaded with politicized connotations.

Given the confusing and high-stakes nature of Guantánamo’s language, students at the University of California, Riverside, felt it was important to create a linguistic “intervention” when the Guantánamo Public Memory Project’s traveling exhibit came to our campus and the California Museum of Photography (CMP). The goal of this intervention was to deconstruct the language that describes and simultaneously obfuscates Guantánamo’s history and to represent – in simplified form – the complex legal documents that dictate the fate of the 166 men still imprisoned there today.

I was one of the public history graduate students who worked on this language component for the exhibition, Geographies of Detention: From Guantánamoto the Golden Gulag, which opened at the CMP on June 1. From the beginning,we were faced with a daunting challenge: How to condense thousands of words of inscrutable legalese into a meaningful and evocative exhibit piece? We found our solution in word clouds.

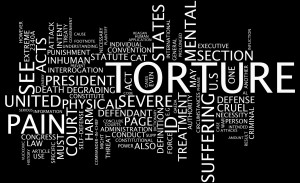

Word clouds are visual depictions of word frequency. The concept is simple – the more a word is used in a text, the larger it appears in the cloud. (We are not the only ones who have found word clouds useful. Students at the University of Minnesota created a word cloud to display the ideas their peers associated with Guantánamo.)

More than just good design, word clouds can expose biases and rhetorical strategies. A striking example of this is the word cloud made from the so-called torture memo, written by Assistant Attorney General Jay S. Bybee. The prominence of the words “torture” and “pain” make clear how explicitly this document talks about humiliating acts of physical and psychological abuse.

But there is also meaning to be found in the small, easily overlooked words in the clouds. Little words, we realized, represented what a text was trying to minimize. In Bybee’s memo, acts of torture are described almost as if they were victimless. In the word cloud this document generates, only a handful of diminutive and impersonal terms – “individual,” “defendant”– reference the people enduring the abuse.

In consultation with our professors and the CMP staff, we decided to turn our word clouds into a video projection. On the second floor of the museum, overlooking paintings and photographs of prisons, hang the traveling panels of the Guantánamo Public Memory Project. The panels line a long catwalk. At its end, the projected word clouds draw visitors’ eyes, and hopefully their interest.

Installation view, Geographies of Detention: From Guantánamo to the Golden Gulag, California Museum of Photography (image courtesy of UCR ARTSblock, photo by Joshua Montez)

The final product ended up being much more expansive than we had originally envisioned. Moving beyond the language of Guantánamo, we considered our local Golden Gulag – California’s extensive prison industrial complex. The Supreme Court has determined that conditions in California prisons to amount to “cruel and unusual punishment.” Despite this ruling, unconstitutional overcrowding continues to this day. By displaying word clouds related to California prisons, we hoped to challenge visitors to think about detention both at Guantánamo and closer to home.

Our ultimate goal was to use the language of detention to tell a new story. In the video projection, key quotes are followed by word clouds generated from the same document. Watching the entire sequence traces the shifting legal definitions and public debates surrounding Guantánamo and California’s Golden Gulag. The projection ends with the Constitution of the United States. For detainees living in legal limbo at Guantánamo and inmates crammed into California’s overcrowded prisons, the rights promised by this document are just words.

The Guantánamo Public Memory Project traveling exhibit will be at UC Riverside until August 10. ‘Geographies of Detention’ will remain on display until September 7.

Posted by Jennifer Thornton, PhD student at the University of California, Riverside

3 Comments to: The Language of Detention

November 17, 2013 5:35 pmEmily Lassiter wrote:

This is a fascinating way of considering U.S. detention policy! As you say, how can a detainee expect to navigate the legal system when the very terms of ‘detention’ are utterly obfuscating? And how are ordinary Americans to realize how invasive and degrading this practice is—much less fight back against it—when it’s couched in such innocuous terms? The world cloud you created is quite striking—I expect that it caused many visitors to think more deeply about the terms of US detention at GTMO. When the GPMP traveling exhibit comes to Greensboro, North Carolina, our class of public history students at UNCG will hold a panel discussion on post-9/11 detention. We’re excited to explore the issues that GTMO raises with legal scholars, former military personnel, and anti-torture activists.

December 8, 2013 12:56 pmwelshd wrote:

While examining Guantanamo and its detention facilities, it is difficult not to immediately think of phrases such as indefinite detention, torture, and enemy combatants. The United States has horrifically mistreated those brought to the base, yet the conditions of domestic prisons filled by citizens of the United States are astonishingly similar. The overwhelming majority of American prisoners can be classified as “second-class” citizens because of their race, socioeconomic status, and/or mental capacities. Though many people attack what they see as imperialist foreign policy and the unconscionable conditions of Guantanamo, they conveniently ignore our own prison system. Prisons in the United States should be just as contested as the detention sites at Guantanamo.

Word clouds, or visual representations of text data, can often shed light on how we conceive of a particular place, event or phenomena. Word clouds that analyze the language used by prison officials, legislators, and policymakers in the United States would no doubt illustrate how Americans categorize and dehumanize, and thus more easily control, the predominantly poor and minority American prison population. While indefinite detention is not an official policy in American prisons, the current justice system is comparable; adequate representation is exceedingly expensive, and once in the American prison system, detainees become more susceptible to returning to prison upon release, because the stigma attached to American prisons and prisoners make it difficult to find and keep decent employment.

-David Welsh, M.A. Candidate at Northeastern University

December 18, 2013 2:11 pmAmber Annis wrote:

What a thought-provoking piece! “Frustratingly indirect” language is exactly what my group members struggle with in our piece for the traveling exhibit. Our project, at the University of Minnesota, examines the comparatives histories of Guantánamo and Ft. Snelling. In the late 19th century, Ft. Snelling was a site of detention for Dakota people during the US/Dakota War of 1862. Over 1600 Dakota women and children were held at the fort after the war ended, with hundreds dying due to inadequate conditions and this site is often referred to as a concentration camp within Dakota communities. Within Ft. Snelling there exist panels that talk about this history in extremely frustrating language. I agree, I think word clouds are a great way to reveal biases and your discussion of the power of them is really useful. Particularly for our project, as we are incorporating word clouds to show how language is important to various institutions. Through your discussion you have led me to revisit our word clouds to focus on those “small, easily over-looked words” as it is often that terminology that holds the most impact. Thank you for your insight and for your important work!

-Amber A. Annis, PhD student in American Studies at University of Minnesota, Twin Cities