Guantánamo: Media Frenzy and Assumed National Access

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

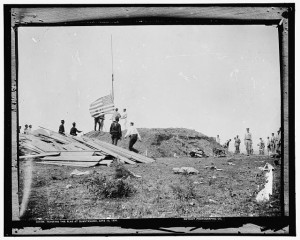

This photograph was captured on June 12, 1898, the moment when U.S. Marines deployed to Guantánamo Bay and hoisted an American flag sent over to their encampment by compatriots on the U.S.S. Marblehead.

This photograph was taken on June 12, 1898 following the Battle of Guantánamo Bay during The Spanish-American War. The raising of the flag, seen here in the aftermath of the battle, has come to signify a turning point in the creation of an overseas American empire.

The brief, formal Spanish-American War moment illustrated here, with soldiers and sailors gathered in rank and file off to the right, has come to represent a symbolic step toward the beginning of continuous U.S. presence at Guantánamo Bay. The image evokes the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima almost 50 years later in the Pacific Theater during World War II. The raising of a flag signifies more than a physical presence of an occupying force in a foreign location; it represents the inception of an overseas American empire through military presence and importation of American culture in Cuba.

The image of the flag hoisting raises some interesting questions about how North Americans receive information and what shapes their perceptions of Guantánamo Bay. The late nineteenth century was characterized by the development of “yellow journalism” and the battles for readers amongst titans of the industry such as Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. One of the most infamous examples of this race to publish was newspaper coverage of the explosion of the U.S.S. Maine on February 15, 1898. Historians have credited the frenzy aroused by the various reports of Spanish attacks on the ship with legitimizing U.S. involvement in the war for the public. The front cover of Hearst’s New York Journal, which featured dramatic titles and promised monetary rewards, was one of the major forces inciting public outcry against Spanish presence in the Americas.

The cover of William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal addressing the February 15, 1898 explosion of the U.S.S. Maine that galvanized American support for The Spanish-American War.

These sorts of hyperbolic press reports have always been a major factor in the perception of Cuba in general, and Guantánamo Bay specifically. The initial descriptions of Cuba circulating in Europe during the seafaring age stressed the fecund nature of the land and the hidden wealth in the silver mines of the New World. Such tales brought Spaniards west to their new colonies in the West Indies. Later reports of extravagant Spanish bullion brought pirates from England and France to the area, as well as bold British colonists from the North American colonies.

Over a century later, the descriptions of the Maine’s sinking bolstered anti-Spanish sentiment in the U.S. When combined with reports and images of the heroic marines challenging the Spanish forces to liberate Cuba, Americans without access to Cuba readily trusted their available news sources for information about the war.

In our culture of constant media updates, Guantánamo, as a liminal space physically outside of the U.S., is still assumed to have some level of access. To this day access to information about Guantánamo is limited to what is filtered through media outlets. We are always a few steps removed from the original source of the information. The race for media exposure and information sharing must be tempered by critical interpretation.

Posted by Zoe Watnik – Ph.D. Candidate at Rutgers University

Rutgers University is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Opening at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery in December 2012 and traveling to 9 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2014, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from US occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.

One Comment to: Guantánamo: Media Frenzy and Assumed National Access

October 31, 2012 1:36 amCarol Wilson wrote:

You bring up an interesting point about information “filters,” such as yellow journalism, that shaped public perceptions of Guantánamo in the past and continue to shape perceptions of the base today. In post-9/11 Guantánamo, journalists are not the only ones who filter information about the base before it passes on to the public. It’s no secret that for reasons of national security, the U.S. military maintains tight control over public knowledge of the base’s activities. Many journalists from around the world have been granted admission to the island during military tours of Guantánamo. Yet during these visits, journalists’ access to the detainee facility is restricted and their photographs and articles are censored. Some journalists and detainees have even claimed that areas of the facility are “staged” during visits to provide a more favorable impression of detainee life. Restricted media access to Guantánamo Bay has limited what the press can convey to the public with certainty and has fostered a culture of secrecy around the base.

Nowhere is this culture of secrecy more apparent than in popular media interpretations of Guantánamo in television shows, novels, and films. From the film Harold and Kumar Escape from Guantánamo Bay to the German mystery novel Guantánamo, Guantánamo Bay has been filtered through the lens of popular culture until the base has become a dark and mysterious place of mythical proportions in the public eye. Does this myth set in stone the public image of Guantánamo and discourage further critical public discussion about the base?

– Carol Wilson, student at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis