Locating in Obscurity: Cuba and Guantánamo Bay

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

Present day Guantánamo Bay is a space that exists in obscurity, both in terms of geography and public imagination. Locating it on a map might involve a simple rendering of the Caribbean islands or, specifically, the southeastern region of Cuba; but to identify the space as a land once colonized by Spain where native Cubans fought for independence, which is currently on lease to the United States, creates a map with more shadowy borders. Why Guantánamo has attracted so many nations involves understanding the broader historical interactions that have made the site so valuable. Exploring the allure of the Cuban landscape illuminates the obscurity surrounding Guantánamo Bay, but also illustrates the multitude of questions that define its contemporary significance.

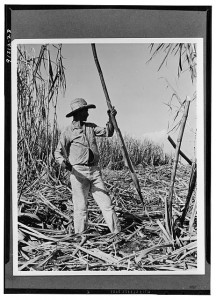

This photograph captures a Cuban sugarcane harvester at work. The importance of sugar cultivation was one of the many economic benefits that influenced Spanish colonial expansion in the Cuban landscape.

The geography of Guantánamo has always involved a contested race for authority, due to its centrality in the Western hemisphere as a gateway for economic opportunity and political authority. On his second voyage in 1494, Christopher Columbus discovered Guantánamo Bay on the southeastern coast of Cuba — a natural harbor with a wide mouth lying low to the ocean and surrounded by a mountain range. From here Columbus encountered Cuba’s natural fecundity: an island that was capable of producing valuable resources such as silver, tobacco, coffee, and sugar. These natural resources (particularly sugar) would ensure Spain’s political dominance over global trade in the Atlantic World, and effectually define the Cuban landscape as an integral economic resource for future colonial enterprises.

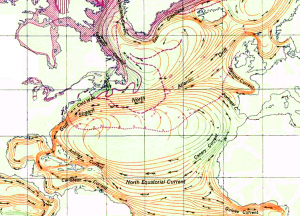

Beyond the bay, Columbus familiarized himself with the complex network of trade winds that centralized Guantánamo Bay within the larger Caribbean Basin. Between Guantánamo Bay and the northwest end of Hispaniola lies one of the busiest sea-lanes in the Western hemisphere—the Windward Passage. Its winds blow ships from the Atlantic into the Caribbean Basin where travelers have total access to the Antilles Islands, the Gulf of Mexico, Central and South America, and – by the twentieth century – even the Pacific Ocean by way of the Panama Canal. This oceanic system effectively unites the global hemispheres, making it ideal for boundless human movement, colonial expansion, and commercial enterprise. Thus, the ecologically complex, secure, and ripe landscape of Guantánamo Bay was an attractive resource for Spanish colonial expansion in the Caribbean Basin, inciting a familiar history of imperial exploitation of commerce in the modern Atlantic World.

This map illustrates the complex oceanic system of currents that define the North Atlantic Gyre. Focussing on Cuba, it is easy to see how it’s position in the mid-Atlantic has defined its centrality in global, sea-faring commerce.

In the late nineteenth century, the United States sought to use Guantánamo Bay as a strategic location to counter the remnants of Spanish colonial rule in the Western Hemisphere. After the outbreak of the Spanish-American War of 1898, U.S. naval forces deployed in the Bay. At the battle of Guantánamo Bay from June 6-10, 1898, U.S. and Cuban troops defeated Spanish forces. The War threw Spain off the seat of world power, and lifted the U.S. to the forefront of global democracy and power. However, the U.S. narrative within Cuba’s independence was also part of a broader imperial program. While encouraging democracy in Cuba, the Cuban-American Treaty of 1903 (coinciding with the Platt Amendment of 1901) transformed Guantánamo Bay into space that produced Cuban sovereignty, but remained under U.S. military jurisdiction. Thus, despite recognizing Cuban independence, U.S. political authority over Guantánamo Naval Base (GTMO) reaffirmed its continued control of a region that had been historically paramount to colonialist strategies, further undermining Cuba’s ability to self-govern.

It is important to mark this event as a shift from the colonial mapping of Guantánamo Bay to the neocolonialist GTMO’s mapping and present day detention camp. This functional change in the region would absorb the consequences of 20th and 21st century foreign affairs, ranging from the 1959 Cuban Revolution, the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, the detention of Haitian refugees during the 1990s, and recent War on Terror detainees. All things considered, the naval base has incited ongoing consternation over an unrecognized diplomatic basis for continued U.S. presence in Guantánamo Bay since the Cuban-American treaty of 1903. With this exceptional status, the base serves U.S. foreign affairs, but not Cuba’s. Thus, with the establishment of U.S. political authority in GTMO, the acknowledgement of Cuba as an independent sovereign state has always remained in question.

Today, the base remains an entangled balancing act of political and national control. But with the recent international focus on 21st century detentions, new obscurities arise from questions over human rights violations and democracy. Does Guantánamo Bay’s exceptional legal status justify the use of the naval base as a detention camp? How many times has the base been “closed,” and what does closure ultimately mean for those who viewed the naval base as important versus those who have been “freed?” These are among the many questions that expose the need for a closer interpretation of the allure of the Cuban landscape, and what makes U.S. control over Guantánamo Bay still vital today. With the changing contexts of Guantánamo’s centrality in world focus, it is important to view the Cuban landscape as a continued narrative of imperial expansion that is evolving with new meanings of global political economy.

Posted by Patrick Ree – MA Candidate at Rutgers University

Rutgers University is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Opening at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery in December 2012 and traveling to 9 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2014, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from US occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.

2 Comments to: Locating in Obscurity: Cuba and Guantánamo Bay

October 5, 2012 2:55 amAmanda Tester wrote:

Patrick, I really enjoyed your perspective. My group is researching the construction of GTMO through the 1960s, and so my frame of reference does not emphasize more recent uses for the base. You mention that trade winds were an important draw for the Spanish to colonize Cuba, but write that American interest in Guantanamo was more imperial. It is true that Americans used the base to project images of power to the world, but a primary function of the base was also to protect trade in the Caribbean- the major period of expansion on the base coincided with WWII when Americans wanted to protect trade routes in the Caribbean.

You ask if GTMO’s exceptional legal status justifies the base being used as a detention camp. Do you think that American politicians intentionally planned for GTMO to be exempt from legal status? I think that the fact that the base was awarded this status over a century ago was a happy coincidence for those looking for a place to detain people. GTMO’s current use was an unintended consequence of decisions made in 1903.

You see GTMO’s presence in the Cuban landscape as “a continued narrative of imperial expansion.” Do you think that GTMO’s location in Cuba is what makes it important, or could we have a detention camp somewhere else in the world and be having this same conversation? Are the current activities going on at GTMO and their implications directly linked Guantanamo’s history when the United States first acquired the base? Has our “narrative of imperial expansion” taken a straight course or turned onto a new path?

– Amanda Tester, student at Arizona State University

October 9, 2012 3:48 amAndrea Field wrote:

Looking at the geography of Guantánamo Bay provides significant insights into the base’s history, as you pointed out in your post. One of the interesting aspects of Guantánamo’s history is the disparity between the fact imperial powers viewed the bay as one of the best natural ports in the world due to its wide mouth, deep water, and strategic location along the Windward Passage, and the reality that, until the Americans built their coaling station, imperial presence in the bay seldom lived up to that potential. One of the ideas we discussed at ASU is that there are really two geographies in Guantánamo: the water geography appealing to naval interests and the land geography that was less appealing to imperial powers. During Spanish rule, the crown continually refused efforts to develop Guantánamo because it was isolated from Havana, the site of political power. The Oriente Province, where Guantánamo is located, was historically Cuba’s “frontier”—available land divided by numerous mountain valleys, making it irregular and useful for small landowners. Isolated from state authority, the province an important source of revolutionary stirrings from the Spanish occupation to Cuban Revolution. The position of Guantánamo within the larger geography of Cuba arguably benefitted the American military base. Naturally protected by mountains on the inland, the base defenses were built up over decades—only building fortifications as threats developed, such as a potential German land invasion during the World Wars or the Castro government’s transition to communism during the Cold War.

I think your connection between geography and the present political conflict around Guantánamo is particularly astute. I would add a question about whether Guantánamo’s physical isolation, both from the United States and the rest of Cuba, was also a consideration in turning the base into a detention camp. Unlike other US permanent foreign bases, Guantánamo is separate from civilian populations. Could this physical isolation have translated into symbolic isolation, making it possible for the events at Guantánamo to be interpreted as outside of international law?

Andrea Field, student at Arizona State University