Telling a Silenced Story

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

Srebrenica, January 1995. Her country in the midst of a civil war, pregnant Hava Muhic, staying in the UN-designated Safe Area, was confident that she would give birth to a healthy and safe child. Half a year later, in July 1995, the baby Hava gave birth to wasn’t breathing and was taken away by the Dutch peacekeeping forces, just days before they failed to protect the camp from an invasion by Serbian military.

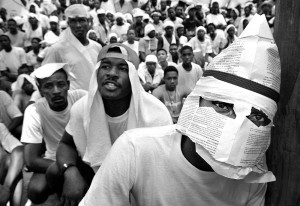

Guantánamo, some three years earlier. Marie Nicole Louis, a Haitian refugee at the base, was told that she suffered complications from her pregnancy: both her twins had to be removed. Months later, while Marie was still waiting for political asylum, a blood test revealed that she had never been pregnant, despite receiving continuous medication and undergoing several surgeries.

Upon starting the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, I had little knowledge of the base’s history. I was shocked to realize that the demeaning and abusive treatment of detainees was a repeated narrative, part of a larger, much more complicated American history. What struck me even more than the experiences of Cuban and Haitian refugees and suspected terrorists is the fact that not just I, but most people with me, had never heard of them (or, at other times, have chosen to disregard the controversies revealed). Why do certain stories go unheard?

When one’s story is part of a larger history of imperialism and Western exceptionalism, one of the principal sufferings is to have this story twisted, if not ignored. The public has been exposed to Guantánamo, the Safe Haven, and Srebrenica, the Safe Area, even though Marie and Hava, rather than feeling protected, found themselves in misery, with insufficient food, lacking medical treatment and derogatory treatment by the American and Dutch forces respectively. The media hailed these forces as rescuers, focusing on the difficulty of their ‘humanitarian’ mission, rather than the experiences of those they ‘rescued’. Shifting the center of attention would, after all, necessarily invoke criticism of U.S. policy and, in the case of the Srebrenica, international governments and the UN.

More difficult than having a story told is how to tell a story. While the Americans at Guantánamo became humanitarian heroes, Haitians were powerless victims, first of a poor and weak Haitian state and later of discriminatory U.S. policies. The Haitians were dehumanized not only during their time at Guantánamo, but also when recollecting it, their identity closely associated with rightlessness, disease and victimhood, making the sharing of their own perspectives even more painful. The dehumanization of the Haitian people is part of a larger historical, racialized discourse, in which the Haitians were dubbed “syphilis-soaked” (Paik, 45) and “absolutely unfit to receive full Constitutional responsibilities and protections” (Kaplan, 842), while graffiti in the Dutch UN-base revealed similar racist comments about Bosnians and the third-world status of their country.

Three years ago, I decided to seek beyond the common narrative and research the faults of my own government, the Netherlands, in Srebrenica. Now, our group tackles the challenge of depicting the Haitian people headed to, staying at, and leaving from Guantánamo. We hope to show both their powerlessness and powerfulness, acknowledge the multiplicity and diversity of their stories, and have the voices, once silenced at the immigration posts and twisted in the media, heard at last.

Posted by Lara Savenije – B.A. Middle East Studies Student at Brown University.

Brown University is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Opening at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery in December 2012 and traveling to 9 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2014, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from US occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.

2 Comments to: Telling a Silenced Story

October 29, 2012 4:55 amThomas Yim wrote:

I really like your observation that the attention was shifted from Haitians’ experiences to the benevolence of western rescuers. This veils the reason why Haitians have those experiences in the first place. The reasoning becomes, “they are suffering, so we should save them!” rather than “why are they suffering in the first place? how to we end the root cause of their sufferings”.

In the same way, this logic, when applied to 911, is “They attacked us! so let’s attack them” rather than “Why did they attack us in the first place? and how do we solve the fundamental force feeding anti-American sentiments”.

It is only when we force ourselves to face the root cause of a problem that we can truly solve it, even though the root cause is often a reality that no one wants to accept.

-Thomas Yim, student at Brown University

November 25, 2012 9:30 pmAngela Thorpe wrote:

Lara,

Similar to you, I was unaware of the history of Guantanamo Bay Navy Base prior to beginning this project. If anything, I understood that the base served as a detention center for those who were a threat to the U.S. Such a simple thought speaks volumes of the power of voice.

Simply put, those who win—or those who are in charge—chose the story that is told. Though this may be unfortunate, I believe it is evident. Consider the Enola Gay controversy: efforts to tell the “entire” story were quickly and aggressively squelched by voices that had power. These voices—congressmen, veterans, etc.—deemed the proposed exhibit un-patriotic. In the eyes of these individuals, the Enola Gay helped the U.S. end a vicious war, and thus, should only be revered. In recent years, a comparable situation can be recognized, in terms of the power of voice as related to Guantanamo Bay. After 9/11, the media painted GTMO as a place where America sent the “bad guys”. Until recent years, any other understanding of GTMO’s role would have been considered un-patriotic, especially in the wake of 9/11. In each situation, the party in charge had the liberty of crafting a story. As public historians, I believe it is our responsibility to tell the stories of those whose voices remain unheard.

Your blog made it clear that, quite frankly, not everyone has a voice, or power to make their voice heard. At UNCG, we struggled similarly with giving equal amounts of agency to those who typically had a voice (U.S. Navy dependents) and those who often went unheard (Cuban base workers). As a result, I understand how you must have struggled with telling the “entire” story and considering multiple perspectives. I think our job would be much simpler if people generally understood that everyone has a story to tell. Unfortunately, not all stories are considered equal, or even relevant. This project may not garner as much recognition as a major news network, yet I would venture to say it is just as powerful. Why? Because we, through our collective efforts, are allowing people to “speak” after they have been silenced for decades. This project, combined with the professional resources we have utilized, is making an effort to tell the “entire” story. That is something that so-called “powerful voices” unable (or unwilling) to do.

-Angela Thorpe

M.A. Candidate at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro