Balancing Acts

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

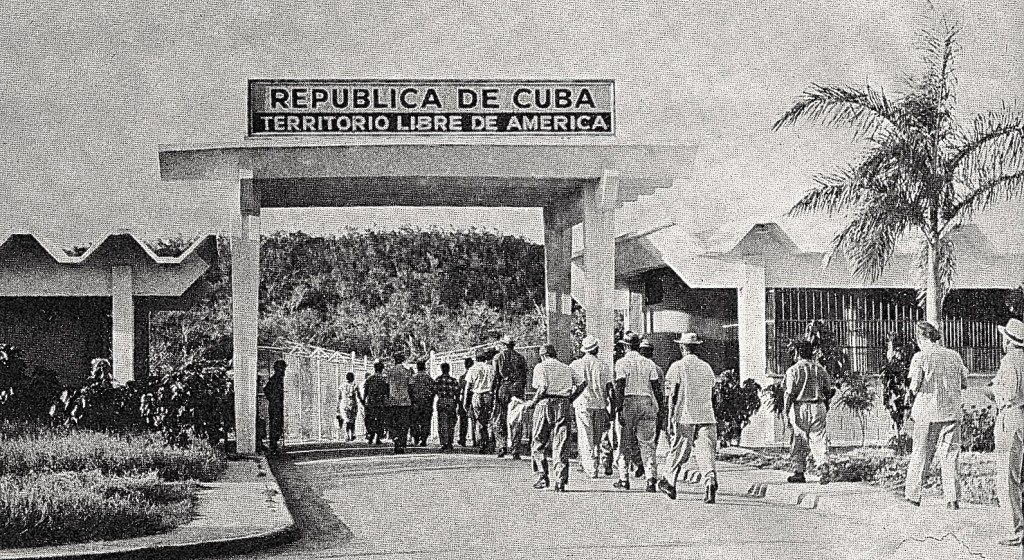

In researching the history of GTMO, I was struck by the delicate balance Cuban workers were forced to maintain between two rival spheres on a day-to-day basis. I found it interesting that, no matter where Cubans traveled between the two separate spheres of the U.S. and Cuba, each dictated in some way, shape, or form, how Cubans were to go about their lives. Specifically, it seemed as if the U.S. sphere on GTMO was responsible for Cubans’ livelihood, while the Cuban sphere outside of GTMO was responsible for Cubans’ lives.

Cuban workers understood this reality: they understood the effects, both positive and negative, that transversing each of these spheres could have upon their lives. Thus, they were constantly required to remain aware of what they did, what they said, whom they socialized with, and what extracurricular activities they were involved in, amongst other things. As we go about our daily lives, are we ever concerned that what we do or say at work, or an association with a friend we may have outside of work, could bring harm to us, or a family member? In most cases, the answer would be no. Thus, I cannot imagine confronting this type of constant, nagging worry on a day-to-day basis.

Developing a more acute understanding of Cuban workers’ lives during the mid-twentieth century has made me more aware of the simple fact that ordinary people carried the burden of two rivaling powers’ quandary every day. Furthermore, they were required to adapt to different ideologies and governance structures fluidly every time they entered GTMO’s gates or exited onto Cuban terrain once more. That, I believe, is an extreme task to undertake successfully. I would hope others would understand the same.

I am not highlighting these findings to say Cuban workers were a skittish bunch that constantly lived in fear; rather, I want others to understand that Cuban workers were required to develop a keen “sixth sense” of awareness, if you will. Fear did not shape each and every of the Cuban workers’ actions; yet they understood that their actions had consequences, whether positive or negative, whether nominal or phenomenal. In essence, their actions were always up for interpretation by two separate governance structures. This is what I hope will be discerned. For how would you adapt to watchful eyes in two contrasting spheres?

Posted by Angela Thorpe-M.A. Candidate at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro

2 Comments to: Balancing Acts

December 10, 2012 2:44 pmLily Nathan wrote:

The Cubans who worked at GTMO during the Cold War are an extreme example, I think, of the way we all deal with competing identities, histories, and cultural expectations on a daily basis.

As I walk New York City’s streets, I navigate not just the physical terrain, but the competing expectations of those I pass. I negotiate between my tendency to zone out, and my need to be safe. At the same time, I balance a desire to be “feminine,” and “fashionable,” with an urge to be utterly unnoticed and invisible. On the subway, I must avoid eye contact, but also make room for the pregnant, disabled, and elderly—and yet somehow shape a temporary space for myself that is sufficiently safe and comfortable to get me through my ride.

The daily negotiations in which we all participate are not nearly as extreme as the ones Cuban workers experienced, nor are the stakes as high. And yet, on some small level, we do all know what it’s like to access different parts of our identity to suit the situation, and to suppress and mask those parts of ourselves that put us in danger.

-Lily Nathan, New York University

December 18, 2012 4:07 pmMegan Greene wrote:

The complex and contradictory daily roles that Cubans working at GTMO had to maintain in order to retain a sense of stability within the two worlds of the US and Cuba are a compelling concept, especially as today, we’re seeing similar issues even closer to home.

Reading this thoughtful post, my mind went immediately to the many rival spheres making up the daily lives of millions of undocumented immigrants living today in the US. The ability to constantly read and represent oneself according to situational expectations is a common human experience, though for both immigrants deemed “illegal” today and for midcentury Cubans working on the base, living just outside its fences, the contrast of daily realities is a stark one. Especially when considering the many personal stories shared of care-free, happy childhoods on-base, the image of Cuban workers employed by the very institution that is taking so many freedoms away from them is a story that also need be told.