Legacy is Knowledge, Legacy is Power

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

Museum exhibits often present stories to engage visitors with the past and encourage contemplation about the legacy of a particular chapter of history. What makes up a place’s legacy? Is it what we have learned from its history? Is it what we still have failed to learn from it?

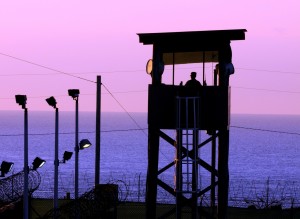

Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Emely Nieves from the Puerto Rico Army National Guard guards her post over the Joint Task Force Guantanamo detention facility at sunrise on January 7, 2011.

I recently read a 2003 article titled “The Legacy of Guantánamo,” written by The Nation’s Lizzy Ratner. In the article, Ratner discusses the lives of three Haitian refugees who were detained in the 1990s at Guantánamo Naval Base, Cuba and the legacy of their internment. One woman interviewed for the article says she relives the experience every day; a man who was only a teenager during his detainment suffers from psychological effects stemming from the experience; and another man included in the article had been gravely ill at GTMO and died days after his release from captivity because he and others were denied proper medical treatment.

Ratner also examines the events that bought the Haitian people to GTMO and the denial of human rights experienced by the detainees. Many Haitian people were forced from their homeland and way of life due to political crisis in which they had little or no power to fight back. When the Haitians sought sanctuary from the United States they were met with imprisonment. According to Ratner many of the Haitian people at GTMO, both HIV positive refugees and their family members experienced further isolation and denial of health care. In addition, some female refuges experienced forced sterilization. After their release from GTMO, and their relocation to the United States, many Haitians experienced continuing physical and psychological effects. According to Lizzy Ratner, “. . . distress was pervasive, and it followed many of the refugees to the United State . . . rage, depression and domestic violence ran rampant”.

These stories brought to mind the treatment that American Indian people experienced at the hands of the United States Government, as well as the lasting effects of generational trauma. Generational trauma perpetuates cycles of psychological sickness that are hard to break and is often transmitted by social learning in the family and community.” It is a permeating sickness that stems displacement, disconnect from their homelands, physical abuse as well as psychological abuse which then manifests into self-loathing, and guilt. Generational trauma experienced by displaced peoples often leads to violence, alcohol abuse, depression, suicide, poor health and poverty. Both Indian people and Haitian were displaced, detained, and denied basic human rights. Apparently the government learned nothing from the legacy of ignoring the rights of displaced peoples.

After generations of pain, American Indian people are fighting back. They are working to regain their lands, build a strong sense of community and identity. But what about the Haitian refugees, what resources are available to them? Who will help them form and amplify a voice?

The Guantánamo Public Memory Project is putting a critical lens to the tumultuous history of GTMO. I am excited that it will travel around the country and will be available online for people to accessible to around the world. A measure of success for this exhibit will be its ability to engage visitors in applying the lessons of Guantánamo’s legacy to issues today.

Posted by Patricia S. Root – Undergraduate student at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities

The University of Minnesota – Twin Cities is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Opening at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery in December 2012 and traveling to 9 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2014, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from US occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.

One Comment to: Legacy is Knowledge, Legacy is Power

December 3, 2012 4:59 pmKelly wrote:

Patricia –

I think you make some great points in your piece – the questions about the importance of history and what exactly we are valuing when producing exhibits on history are right on point with this project and exhibit.

I appreciate the connection you make between Haitian refugees at Guantanamo Bay and the treatment of Native Americans in US history, though I’m not sure the experiences can be paralleled so directly. It is true that both Native Americans and Haitian refugees experienced displacement, but the circumstances leading up to and, in the case of Native Americans, sustaining this are quite different. For Native Americans, leaving their homelands was often not done by choice; the histories of colonial and missionary relations in the United States are exceedingly lengthy and complex. It was, however, based within America, between Americans. Haitian refugees sought refuge in America, choosing to flee their country because of political unrest and fear of persecution. Certainly, it may have felt like a forced decision to many, but the final decision was still that of each individual, a choice that Native Americans were largely deprived of.

You claim that, when dealing with Haitian refugees detained at Guantanamo, the US government failed to draw on lessons learned through the history of Native American mistreatment. I do not think this is the case. The government itself was the cause of displacement and rightlessness experienced by Native Americans. They did not simply ignore the rights of displaced Native Americans – they initiated and perpetuated the loss of rights. The Haitian refugees sought solace in the United States and were met with a government unsure of how to deal with the influx of people. While the government may not have had a ‘legacy’ from the past to draw on for guidance when dealing with the Haitian refugees, the hope is that they will use that experience to inform future action, should the need arise.

— Kelly Gauvin, MA Museum Studies, New York University