To Explore Guantánamo Is To Explore Empire

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

I did not truly begin to understand imperialism until I read modern Arabic literature in an undergraduate course at Rutgers. Though I had long been aware of empires as a concept, I had no grasp of what imperialism could mean to an individual until I read narratives written from the perspective of the colonized. I was awakened to the way my own family’s experiences have been shaped by Britain’s colonization of India, and how extensive those impacts are – from the language my grandparents speak to the place my parents live. The new understanding was painful, not least because it was a simultaneous awakening to the troubling, Imperial history of America, my homeland.

Guantánamo Bay is to me one of the most tangible symbols of that living history. It took great force of will to try to contemplate the experiences of people currently detained at this prison, and to watch interviews with former post-9/11 detainees. I realized that these were people with whom I had little in common, other than perhaps the color of our skin, or the language of our names, or the name of our God, if even that. Though I had experienced some hate crimes that were born of Islamophobia in post 9/11 America, I was unsure if it was even my place to give voice to the horrific experiences of the detainees, that had never scarred my own flesh and soul.

At one of our first rehearsals, I realized that my teammates (Alyea Pierce and Dennis Sholler) faced even larger barriers to entering into the voices of Cuban or Haitian refugees who had been detained at Guantanamo – barriers of time, of language and of race. Watching them delve into the experiences of these people, to bring forth voices submerged in the not-so-distant past, made me realize that there are aspects of our shared human experience that would provide powerful bridges between us and the detainees. A longing for a safe home, for escape from a desperate situation, the pain of separation from family members, and the hopeless fear of circumstances or illnesses beyond one’s control were themes that emerged strongly in all of our writing, partly because we too had felt these emotions on some level. My understanding of the performance’s purpose finally became focused around bringing the humanity of the detainees as close as possible to the audience, in order to bring the injustice of their detainment that much closer.

In trying to capture the perspective of a post 9/11 detainee, I found myself speaking also of a sense of an American’s betrayal by America as a whole, and specifically by the American people who did not stop the government’s continued detention of people being held without due process and without being convicted of a crime. Every moment of the performance, while voicing the slow and painful destruction of an inmate, I was aware that the burden of ending this injustice is as much my own as any other citizen’s. Bringing the weight and immediacy of that duty closer to my own heart was one of the most important parts of the experience. I hope I was able to do the same for others, in some small way.

Shireen Hamza is a student at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

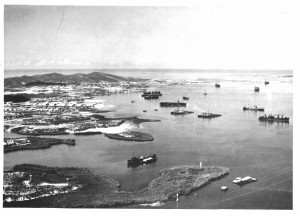

Rutgers University is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Traveling to 12 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2015, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from U.S. occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.