The Representation of GTMO Through Photography: Partial Truths?

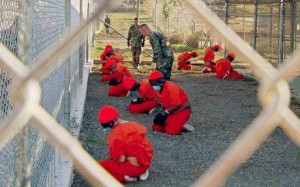

Whilst taking the module ‘Ethics of Representation’, as part of my MA at the University of Brighton, part of my study has been to view photographs and discuss the ethical implications of taking and viewing such images; particularly those which portray scenes of conflict or humanitarian crisis. Whilst researching images of this nature I viewed several photographs from GTMO and noted a recurring theme; despite the length of time that GTMO has been operating the photographs that have been released only portray a selected view of the activities that are undertaken there.

It is clear that this restricted view of GTMO is a result of the strict censorship rules and restrictions imposed on visiting photographers. Subsequently the pictures released do not capture the numerous first-hand accounts of torture and abuse of human rights in their totality. But this restricted view led me to ask what the purpose of allowing the release of any photographs from GTMO is if they do not allow the complete picture to be seen? Why release these images if they only depict a partial truth? Is the restricted view of GTMO presented in the naive belief that it will convince the public that the images released represent the entirety of activities undertaken? Is this restricted view drip fed to the public in the fear that releasing no images would validate the accounts of abuse and cause the public to further condemn the activities taking place? Or is this view intentionally restricted and released to the public to remind viewers of what the images do not portray, as a warning, as a insinuation of the oppressive force that can be deployed if the controlling powers feel it necessary, as a form of Panopticism?

I raise the above questions not out of desire for an immediate answer but for reflection. To allow us to consider whether the power of what is not shown within the photographs released from GTMO is stronger than what is shown? Both Susan Sontag and Judith Butler explore at length the power of photography and the importance of how the image is framed, not physically but metaphysically, affects the interpretation of the photography itself. Of how the interpretation of an image can be influenced by a viewer’s contextual knowledge. It could therefore be argued that the absence of the full pictorial representation of GTMO is more powerful than what is shown but only if the picture can be properly framed by contextual knowledge. Therefore it is vital that as much explorative work and research surrounding Guantánamo is completed to allow for the appropriate framing of any images released. Such work will allow the photographical representation of GTMO to be considered in its entirety even if the photographs released depict only a partial truth.

Posted by Frank Melmoe – MA Candidate at Brighton University, England.