Reflection: Guantánamo Bay – Collective Confusion and Misinformation

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit | Reflection + Action

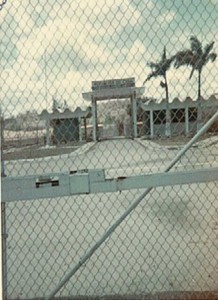

Northeast gate of Guantánamo Naval base, facing “Castro side,” circa 1965 – Photo courtesy Anita Lewis-Isom

While learning the history of the Guantánamo Naval base (GTMO), time and time again I’ve been struck by a sense of collective confusion and misinformation that has reappeared in the stories of people stationed at the base, as well as detainees and non-American workers who have lived there.

The base has often been used as a hasty solution to problems arising from inadequate immigration policies and the U.S. government’s lack of commitment or responsibility. The fact that GTMO’s appeal, and its selection for usage, is predicated by its “legal loophole” status is incredibly disturbing. It implies that the American justice system, the supposed model of sociopolitical order, is entirely expendable when the government decides so, and sends the message that Americans believe that our government is above every law on earth, including our own.

One question in particular has been recurring throughout our class discussions. Surely there must be other sites similar to Guantánamo where Americans are committing atrocities outside of any legal jurisdiction, all in the name of preserving democracy. Why are so many Americans willing to turn a blind eye to these events? Are we willing to accept the cost of maintaining our position as an international superpower and police force, or is it something more frighteningly apathetic—i.e., it hard for us to care if these events do not disturb our comfortable lifestyles or immediately impact our lives? Have we become desensitized to the sensational media, or is it because we aren’t demanding more transparency from our government? Do we even want to?

I realize these questions are not objective, but I believe they are worth asking. Within these discussions I would ideally like to involve members of the media who’ve reported on GTMO and politicians and military personnel who’ve influenced decisions in regards to the base. We often hear that actions are merely orders being carried out—orders issued by whom? Where does it begin?

By Laura Keller, Public History Program, Arizona State University

Arizona State University is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Opening at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery in December 2012 and traveling to 9 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2014, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from US occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.

3 Comments to: Reflection: Guantánamo Bay – Collective Confusion and Misinformation

May 4, 2012 7:07 pmAmanda wrote:

This interview with al-Rawi was very capaivtting. He’s an engaging man with a hell of a story. Beyond the interview, this reflection piece by Schmidl is also interesting I agree totally, Guantanamo is a place where people lose their minds does stick out, and does capture the main idea of al-Rawi’s experience. The piece is compelling because I’d bet that stories like these are not easily aired on T.V., as they are likely shunned from popular American media platforms. Honestly, how often does the American public hear stories like this directly from the source? Rarely, if ever. Actually hearing this personal story from al-Rawi, as opposed to a news anchor, a journalist, or a politician, adds an emotional element and a sense of pain and reality, which makes this interview gritty yet eloquent, and hard to forget. Also, al-Rawi ends his interview on an idealistic note, advocating that all suspected criminals/terrorists should have their day in court . Honestly, I have been skeptical about this idea, but after hearing al-Rawi’s story, and the injustices he has endured over such an extended period of time, I find myself much more open to his suggestion. Overall, as an American citizen, it is important to hear POV’s like this so that we are better informed and more aware of what is going on (or what has already transpired) at GTMO. At the very least, with more exposure of people like al-Rawi, Americans should be (and need to be) better informed, especially by sources outside of the major U.S. news outlets, which the Guantanamo Public Memory Project seemingly seeks to achieve.

October 11, 2012 1:05 pmKaelynn Hayes wrote:

Within this post, I found many of the same questions that have gone through my mind since my class began research for our post-9/11 GTMO panel. I chose to examine the Bush administration’s claim that the Geneva Conventions did not apply to al-Qaeda or Taliban detainees. You ask where the orders carried out at GTMO originate. In this case, President Bush followed legal advice from the Department of Justice and ignored protests from other legal advisors as well as military officers. Those who objected realized that abandoning the Conventions would harm America’s global reputation and put U.S. military members at risk of being charged with war crimes.

While I focused my research on the government’s actions at GTMO, your post made me consider the perspective of the American public on the Bush administration’s decisions. As you pointed out, people usually do not care about things that do not directly disrupt their own lives. In addition to being apathetic, I think many Americans assumed that the government was doing what was necessary to prevent another terrorist attack. At the time, they probably did not realize that abandoning the Conventions would lead to torture and the denial of legal rights for GTMO detainees. Having seen the human rights abuses that resulted, I hope that Americans will not continue to blindly accept the government’s national security decisions. Perhaps public outrage could have prevented the mistreatment of hundreds of GTMO detainees.

Posted by Kaelynn Hayes — MA Candidate at IUPUI

December 8, 2012 6:27 pmSarah Emmel wrote:

The thought, “Surely there must be other sites similar to Guantánamo where Americans are committing atrocities outside of any legal jurisdiction,” had occurred to me as well during our group’s investigation into our panel’s theme regarding the future of GTMO. Along with your questions about the American public being willing to turn a blind eye to the situation, I began to wonder if it would even be constructive to push for the “closing” of the base. If the US is going to have these detention centers somewhere (as, it seems, they inevitably will) wouldn’t it be better for it to be in a location that the public and the media are already aware of? Does GTMO benefit from having been the subject of protest and political attention, so that Americans will be more focused on further deterioration of conditions there–instead of it being hidden at another location out of the public consciousness? Or does this exposure desensitize the public to the point where their knowledge of the situation makes them less likely to be appalled or speak out at all?

Perhaps with more in depth dialogue like this, people could become aware of GTMO’s context in history, human rights, and legal standards. The public could possess a meaningful awareness of the situation in order to keep it in check–at least until the US government, due to international or domestic pressure, ceases to use any of these extralegal measures to “preserve democracy.”