Peace and Solitude: A New Perspective about Life at GTMO

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

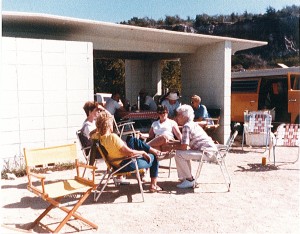

The Williams family relaxing and socializing with friends and colleagues during a “beach day” at Kittery Beach, GTMO. Photo courtesy of Winston and Nelda Williams.

If you stopped a person on any street in America today and asked them what they thought about the U.S. naval station at Guantánamo Bay, chances are, you would hear a response about “detainees,” “torture,” or the “War on Terror.” If you asked a person who has lived or served at GTMO that same question, however, you are liable to hear the words “paradise” or “Mayberry”. While there is no denying or minimizing the presence and role of the detention camp in the history of the site, there is more to the long history of the base than what has happened there in the last ten years.

I too had my own preconceived notions about GTMO when I first became involved with the Guantánamo Public Memory Project through the University of West Florida’s Public History program in the summer of 2012. My first thoughts about the base conjured up images of detainees clad in orange jumpsuits and handcuffed behind chain link fences and razor wire. After studying the history of the base and, more importantly, meeting with and interviewing people who had lived there, I came away with an entirely new perspective. I realized that GTMO was a place where thousands of Americans had served their country, where children were born and raised, and where people came together and formed an extremely close-knit community under circumstances unlike anywhere else in the world.

When speaking with those who lived at the US naval station at Guantánamo Bay, I found they rarely had negative things to say about the site. The majority of people I interviewed over the summer said they did not want to leave and would jump at the chance to go back. One couple in particular stands out.

Winston and Nelda Williams made GTMO their home over the course of four decades from the 1960s through the 1990s. They moved from the base on three occasions and each time could not stay away. If they could have retired down there, they said, they would have. Living in Guantánamo Bay at different times through four decades provided the Williams family with a unique perspective on the history of the base. They witnessed the changes that came with the advancements of technology, from having a military transport fly in the tape of the Super Bowl on Monday during the 1970s to satellite television in the 1990s, but the close-knit nature of the community largely remained the same. In all the time they spent there, they never locked the doors to their house or car. For the Williams family, Guantánamo provided “peace and solitude that cannot be found anywhere else.”

The same sentiments were echoed by many, including Barbara Phipps, a member of the Navy WAVES in the 1970s. For her GTMO was a place full of adventure and opportunity. While serving at the US naval station at Guantánamo Bay she learned how to square dance and how to sail, she played tennis and golf, bowled, and went snorkeling and swimming at the beaches. Like most people who have lived at GTMO, she never worried about locking her house or car because “there was no crime”. When describing the uniqueness of the community at Guantánamo she said, “Everybody knew everybody; you never met a stranger down there.” She too, longed to stay at GTMO but she had already extended her tour once already.

As a historian, it is essential to understand that nothing is ever black or white. To only view Guantánamo as a symbol of American Imperialism or the War on Terror would be a mistake. While those events are important in the base’s history, they alone do not define GTMO. It would also be remiss to completely dismiss the controversy and negative aspects of the base. To fully comprehend the dynamics of the base and gain a better understanding of its history, it is necessary to speak to the men and women who served and lived there. To foster a complete discussion about GTMO and what it symbolizes, we as historians must recognize and set aside our preconceived notions and realize that it means different things to different people and that the truth lies somewhere in between. When we do that, we will come away with a more complete and accurate history of the US naval station at Guantánamo Bay.

Posted by Sean Baker – M.A. Candidate at the University of West Florida

The University of West Florida is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Opening at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery in December 2012 and traveling to 9 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2014, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from US occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.

3 Comments to: Peace and Solitude: A New Perspective about Life at GTMO

November 26, 2012 9:38 pmLeigh Smith wrote:

I too had preconceived notions about the US Naval Station at Guantanamo Bay. The only knowledge I had of GTMO was that of the post 9/11 detention camps. As part of this project, my classmates and I interviewed several individuals who lived at GTMO during the 1960s. It certainly put GTMO into perspective. Like Sean, I realized that the individuals living on base were part of an extraordinarily close community- especially given the tensions of the Cold War. I completely agree that we cannot view Guantanamo as a symbol of American Imperialism or the War on Terror. This would trivialize the lives and contributions of thousands of individuals- American, Cuban, Jamaican, etc. – who lived there. GTMO cannot be defined by recent headlines. We should look beyond the headlines to the individuals who lived there. That’s why I think the oral histories that we have completed are so important. They give the individuals who lived there a voice and help fill in a few of the silences in the history of GTMO.

Leigh Smith- MA Candidate, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

December 1, 2012 5:23 pmMeghan Reed wrote:

There is definitely a fixed notion of Guantánamo in the mind of most Americans. The idea of the base as a torture facility will probably prevail for quite some time, and it is because of this that I find the Guantánamo Public Memory Project so important. There are, as you mention, so many dependents that wish for a chance to go back to that life. Janet Miller discusses her experiences in such a positive way, mentioning the everyday frustrations but moving past them to describe a world that she wishes she could again be part of. Dale Ward Gordon, who spent her entire teenage years at Guantánamo, echoes those same sentiments as well as hoping that she will be able to meet her school friends again, as they are now living in many different parts of the county. I also was very struck by your statement that everything is never black or white, as that is so true! Sure, everyone at Guantánamo had different experiences, and it would be a mistake to assume that everyone had this semi-idealistic experience while living on the base. The Cubans and Haitians did not live the same lives as the American dependents, and we should not overlook those memories that conflict with this idealist image. In order to look past Guantánamo and to see its potential, I feel that it is vital to understand how it can be. The dependents experiences on the base should reflect a new hope for Guantánamo’s future.

Meghan Reed—MA Candidate, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

December 18, 2012 5:43 pmBen Frank wrote:

Sean,

Thank you for your work in bringing these stories to light. I am also fascinated to read accounts of GTMO base life as it was in the 1960s and beyond.

As an Urban Studies undergraduate, the “Mayberry” memories of people who lived or served at GTMO show me connections between life there and American ideals at the time. At the height of urban exodus, U.S. suburbs promised a clean and beautiful environment surrounded by nature, a place of true “peace and solitude” where outside threat was non-existent. Everyone is a friend and nothing is ever wrongful taken. It seems logical that such an idyllic life would be reproduced at GTMO. At the same time, the stateside contrast of a created “paradise” to a troubled city makes me wonder if GTMO base life was a simple construct to beautify and ease the difficulty of living and working outside the country.

What sort of experience is recalled at other military bases? Where are stories of hardship GTMO base families faced? And what sort of stories do GTMO base families share of life before arriving to “paradise?”

Ben Frank– University of Minnesota