Restricted Reading

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

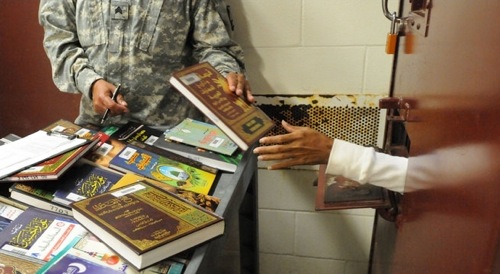

Guantánamo prisoner browses books from the detainee library.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Navy, in the Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

There is a never-ending debate in library science on what types of content should be withheld from the bookshelves. Subjects like pornography seem like a universal “no.” But between the obvious “yeses” and “noes,” there are shades of gray, as with the recent controversy over the popular E.L. James novel. Without clear-cut lines, it is left to librarians to evaluate the wants and needs of their patrons and to provide material that they consider to be in the best interest of the community.

But what if that community is composed of alleged terrorists? How do you determine what types of content should be provided? In November of 2009, the Miami Herald released a list of guidelines used by the detainee library at the naval base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. To promote intellectual stimulation among the detainees, the library authorizes material in the sciences and humanities. These subjects include astronomy, marine biology, art, and poetry, among many others you would find in your local library. But there is also a lengthy list of content restricted for security reasons. Much information on physical geography is unavailable to limit access to details on buildings or transportation—potential terrorist targets. Books are screened for what is determined to be extremist or militant ideologies. The high-security detention prison also has a very scant travel section.

So what kind of books do the detainees read? A Miami Herald article published November 28, 2010 provides details from court proceedings of confessed terrorist Omar Khadr. Entered as evidence, his library reading list contains familiar books like Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father, Nelson Mandela’s Walk to Freedom and books from the Harry Potter and Twilight series.

In addition to offering books and other materials, libraries offer an increasing amount of engaging educational programs. This applies to Guantánamo as well. A recent government report, reviewing detainee conditions and confinement, contains a section on intellectual stimulation. The Guantánamo detainees have access to library programs and classes in literacy, foreign languages, and art—similar to programs being offered at just about any neighborhood library. In the same document, there is a recommendation to further expand these intellectual stimulation programs.

The library science community utilizes social media and conferences for discussion among professionals. A common theme of these discussions focuses on how to target the varied interests and needs of different libraries. After all, not every community is the same. Differences in language, age, and socioeconomic conditions exist, despite the common goals and values that all libraries share.

In the detainee library at Guantánamo, we see material and programs that seem very familiar to many people. We see Harry Potter books and art classes. But the library collection is also specialized for this community with material in 18 languages native to the detainees. The detainees are encouraged to develop skills that would be useful if and when they are reintegrated into society. We also see a scaled-up version of the common library collections dilemma—what content should we not be providing? Here, what content poses a threat to national security?

While I acknowledge that the detainee library at Guantánamo must operate under more strict limitations, it is important that this community continue to have access to material and programs that allow them to learn, to discover and to create. I believe that is what all libraries are for—even in a remote, chaotic and seemingly lawless place like Guantánamo Bay.

Posted by Zachary Mohlis – BA History at the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Opening at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery in December 2012 and traveling to 9 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2014, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from US occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.

2 Comments to: Restricted Reading

October 29, 2012 8:06 pmPhilip Johnson wrote:

I really enjoyed this post – it highlighted an aspect of the detainee experience in Guantánamo that I hadn’t otherwise considered during this course.

Of particular interest to me was the way education (and I’m sorry if I’m taking this in a direct completely unrelated to what was intended by this piece) and the library is situated at an intersection between punishment and rehabilitation, between censorship and opportunity.

The offerings in the detainee library can, it seems to me, be read as an example of the extent of coercion within the facility, another measure of just how repentant a detainee is, just how well socialised, reformed, and westernised. This is a pretty Foucauldian approach: education as socialisation into expected norms and functions of the dominant power. Turning potential enemies of the state into docile, Harry Potter-reading bodies.

Taking this to an extreme, it is a reminder of the work of Gramsci, Bourdieu and friends, who would say that as social control develops, the need for physical repression diminishes. I suppose in theory, if you get the reading list and education programs running effectively enough, then the cells, fences and guards become unnecessary. Eventually the detainees will only want to read what they ought to read. Eventually they’ll be thoroughly domesticated – they’ll even become useful social instruments.

Equally, however, the library can be viewed as one of the most optimistic features of the detention facility, suggesting that the right sort of reading material may offer a path out of extremism, or despair, or just of indefinite detention. This view is exemplified by Martha Nussbaum, who sees literature, and the act of reading itself, as the means of creating compassionate, informed citizens (not that any detainee is likely to become an American citizen any time soon). This is a highly idealistic approach, attributing almost mystic transformative power to the book, but in a sense, this is absolutely necessary for an educational project. Without some ideal to strive towards, where does education lead?

This article has a picture of Guantánamo’s ‘reading room’, circa 1996. There is a conspicuous lack of anything to read.

http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/hickss-window-on-the-world/2006/11/27/1164476134575.html

Posted by Philip Johnson – M.A. candidate at NYU.

November 13, 2012 6:59 pmZachary Mohlis wrote:

You bring up some great points, Philip. As far as I have seen, the military supplies a library and materials for the purpose of “intellectual stimulation.” The question, then, is what is the goal of this “intellectual stimulation?” Whether it is to further control/domesticate or to inspire and help them develop, we just don’t have enough information to know for sure.

And I seriously doubt that those responsible for running the library know what the goal is either. It seems that the detainee library is currently haphazardly thrown together and lacking a true purpose. There is plenty of material, but irregular access. Some shelves look full, but not necessarily in the reading rooms for detainees.

I’d rather not see the prison camp remain operational, but if that is to be, then further discussion needs to be had in order to determine the purpose and goal of the library.

Zachary Mohlis, student at University of Minnesota, Twin Cities