This Week in Guantánamo: 2013 and 1927

This Week in Guantánamo: Present and Past

This week, in 1927, writer K. C. McIntosh published an article on Guantánamo for the American Mercury, in which he described a scene of U.S. sailors drinking merrily at a tavern in nearby Caimanera, Cuba.

The bartenders, soaked with perspiration and the splash of upset glasses, pass out the last round. Lean, nondescript dogs, their eyes glazed with unaccustomed gorging of chicken-bones, lurch under the tables. The red-haired youngster on top of the piano raises his seidel and his high full tenor voice rings out,

We’re sitting on top of the world.

Just steaming along—

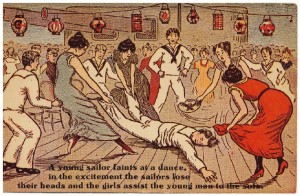

“A young sailor faints at a dance, in the excitement the sailors lose their heads and the girls assist the young man to the sofa.” Image courtesy of Guantanamo Naval Station Public Affairs Office. Date unknown.

This week also marked the 11 year anniversary of the arrival of the first “enemy combatants” at Guantánamo under the “War on Terror.” Since January 2002 the site has held a total of 779 people from around the world without charge, outside the legal protections mandated by U.S. law. The youngest only thirteen, the oldest ninety-eight, these detainees were denied POW status and the corresponding rights guaranteed by the Geneva Convention––including judicial review and protection from torture. The majority of them have been repatriated to the various countries from which they were taken by C.I.A. and U.S. military officials. The last 166 remain indefinitely detained, as U.S. leaders and the public debate their futures.

The contrast presented between Guantánamo the beloved naval outpost and Guantánamo the indefinite detention facility raises important questions about the process of engaging the site’s history. How can we study Guantánamo’s past from multiple perspectives, and without disproportionately focusing on the site’s latest use in the post-9/11 world? At the same time, how can we examine the past without distracting attention from the urgent issues of the present?

An “enemy combatant” is transported at the Guantánamo Bay detention facility. February 2002. Image courtesy of Associated Press.

At the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, we address these questions by inviting robust dialogue about the site from people representing diverse perspectives and experiences. Please feel free to add your take in the comments section, and explore our website to learn more about how you can join the national dialogue on Guantánamo.

You can contact the Guantánamo Public Memory Project at guantanamo@columbia.edu