“Accommodating ‘our boys’ in ways Mother never intended”: The Sexual Politics of Guantánamo Bay

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

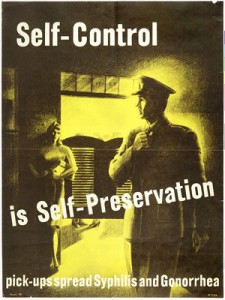

A typical military-issued PSA about the sources of venereal disease. Within the door of the bar, the shoes of a soldier and his “good-time girl” are visible, hinting at his ill prospects.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the regular enlisted men of the U.S. Navy stationed at Guantánamo Bay were enmeshed in a culture of intense masculinity and sexual isolation, with no American women on the base, except for the wives of high-ranking officers. The raucous activities that took place just outside the walls of the naval base, in the towns of the Oriente province, were characteristic of the lax attitudes and laidback spirit of the U.S. Navy. Quietly ignored by the officers, their actions were typical of the early years on the base. This sort of mentality toward the Cubans and their culture certainly played into the development of anti-U.S. sentiment in the years predating the rise of Castro.

As the first base acquired by the recently formed American overseas empire, the sparsely populated coaling station, situated in a protected natural harbor on the coast of a tropical island, was an incredibly dull assignment for seamen. The base itself saw U.S. naval ships dock for recoaling while cruising the Caribbean territories, but very limited action through the various wars of the twentieth century. For Navy men, the break from the humdrum life on the base was the Liberty Tour, essentially a weekend off. During this period, the men could leave the base for a jaunt to the nearby Cuban towns of Caimanera or Guantánamo City, or even farther afield to neighboring islands like Haiti and Jamaica. The towns outside the naval base became the points of cultural encounters, where sailors interacted with Cubans and other native residents of the West Indies. More often than not, these points of contact were characterized by sex, where the burden of white masculinity, typically perceived as a duty to maintain “civilized” and respectable behavior back in the U.S., could be relinquished in the presence of the “wild” and sexualized native women of the tropics.

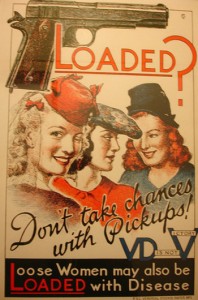

The types of VD posters illustrated above from other American naval outposts would have most likely been present at Guantánamo Bay as well. These types of resources were commissioned by the US military as a method to keep the men disease free and fighting fit. Despite the heroic imagery and confrontational messages, the public health initiatives of the military were complemented by more direct action, like free prophylaxis and penicillin dispensaries at the entrance to the red light districts.

Puns and double entendres proliferated in these types of posters, and the warnings they offer are lighthearted, yet staunch. In this poster, sexuality becomes militarized, and “pickups” are depicted as threats akin to the enemy on the battlefield. Despite the presence of these PSAs on US naval bases around the world, the men never stopped visiting available women.

The existence of the base in the Oriente province created situations of extreme poverty for many of the women living in the area as the economy of the region shifted to cater to sailors and their pleasures. Officers and enlisted men who visited towns like Caimanera on their Liberty Tours described the city “as a large-scale brothel for accommodating ‘our boys’ in ways Mother never intended.” Although never officially sanctioned, these relations were tacitly accepted as part of the world of the naval base. Men from the base were stationed on shore patrol near the brothels along the harbor, where they monitored the enlisted men on leave, ensuring that violence did not break out.

The US presence radically altered the economy of Caimanera and other cities as sailors were allowed to run amok in the Cuban territory with impunity. Ironically, at Guantánamo, US control, though localized, brought the additional burden of widespread economic reliance on the naval base. With the weight of empire behind the sailors, these individual contact points allowed the micropolitics of empire to play out in these areas of intimacy. Although the Cuban accounts regarding these points of cultural interaction have been elided from the more usual narratives of U.S. involvement in Cuba, an investigation of these interactions, typically accepted silently by the Navy, yields an interesting component to the framework behind the sentiments of the cross-national Cold War relations that would follow in later years.

Posted by Zoe Watnik – Ph.D. Candidate at Rutgers University

Rutgers University is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Opening at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery in December 2012 and traveling to 9 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2014, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from US occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.

One Comment to: “Accommodating ‘our boys’ in ways Mother never intended”: The Sexual Politics of Guantánamo Bay

October 23, 2012 9:27 pmKavita Singh wrote:

Like most aspects of GTMO’s history, the sexual exploits of the U.S. Navy has a clandestine nature surrounding it. While reading this post, I was not surprised by the actions of the officers and enlisted men, since rumors of disreputable sexual behavior from members of the U.S. military are not unheard of, especially during a time when Cuba was viewed by the U.S. as a playground for licentious behavior. However, it made me contemplate how the actions of these military officials have evolved over the last century and how comparable their actions are presently. How often are the same “raucous activities” currently taking place in countries across the globe, where we are stationed, and have any measures been taken to ensure that the behavior of these men are being monitored? Considering the secrecy behind the actions in Cuba at the turn of the twentieth century, it is plausible that U.S. Army officials are still accommodating or ignoring the sexual mishaps occurring overseas. Taking this into consideration, the effect of these actions pose a serious threat to our nation’s identity overseas. Additionally, they could contribute to anti-U.S. sentiment and negative relations with foreign countries, reflecting an attitude that does not summate to our country’s ideals. While we may never hear the accounts of the Cuban women who were used for sexual exploitation, their encounters with American military men could offer an interesting perspective on U.S. presence in Cuba during the early twentieth century, and possibly activate change in military behavior overseas.

– Kavita Singh, student at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis