The Protectorate?: US Paternalism in the Conception of Guantánamo

National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit

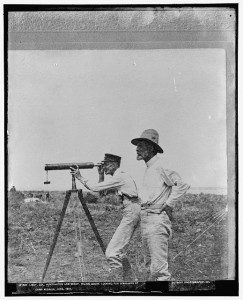

U.S. government prospectors examine the land surrounding Guantánamo Bay, Cuba for signs that it can be utilized militarily. 1900-1903. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In June of 1898 the US began its occupation on the beaches of Guantánamo Bay in order to help Cuba in their fight for independence from Spanish rule. This larger conflict would later be known as the Spanish-American War.

In August of 1898, Spain relinquished control over Cuba. However the US government and “most Americans had no faith that Cuba could govern itself” (Hansen, Guantánamo 2011). Because the US put itself in the middle of this conflict, many Americans now believed that it was in every one’s best interest to continue to occupy and provide security for the stability of Cuba’s new government. This of course, was crushing to the Cuban wish for a free state under the rule of no other country.

This was the beginning of a long trend in US policy towards imperialism and paternalistic tendencies in Cuba (and around the globe). This was an effort by the US Government to secure the extraction of resources and the establishment of mainly strategic naval outposts; Guantánamo Bay being among them. All policies enacted in the following years to facilitate these aforementioned goals were directly due to the overall belief in the American government and society that Cuba was simply unable to control its own affairs.

Today no one would argue that Cuba is unable to function on its own; in fact it might be among the most autonomous countries in the world. Yet, from the days of US occupation in Cuba, the US still has been able to keep control over Guantánamo Bay as a naval base and now mainly a detention center for “The War on Terror”.

What struck me most about the continued use of the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base is that the site came from the conception of world policing and continues to be used for the same purposes under a different function nearly a century later. Guantánamo is also entirely outside of US law, although technically under Cuban jurisdiction, which means that in reality it is a “legal black hole” (Kaplan, Where is Guantánamo?, 2005). This legal unreliability leads to a stronger sense of US paternalism essentially saying that the US government and military know better how to handle these prisoners than do the US courts and conventional law. Is this really how we as Americans want to be seen across the world and does it match up with US values in foreign policy?

There are currently 167 detainees at Guantánamo, “only a couple convicted, and the rest, either awaiting trial, designated for indefinite detention, or just being held until somebody figures out a solution” (Carol Rosenberg, Miami Herald, 2012). The US Government needs to be consistent and more transparent with any prisoner regardless of the degree of accused crime, otherwise the fate of these men will be left up to conjecture. Guantánamo, under no circumstance, should be an exception unless we all truly believe the US government knows best.

– Posted by Parker Hoffman, Undergraduate student at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities

The University of Minnesota – Twin Cities is participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project‘s National Dialogue and Traveling Exhibit. Opening at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery in December 2012 and traveling to 9 sites (and counting) across the country through at least 2014, the exhibit will explore GTMO’s history from US occupation in 1898 to today’s debates and visions for its future. The exhibit is being developed through a unique collaboration among a growing number of universities as a dialogue among their students, communities, and people with first-hand experience at GTMO.